The Significance of Shrek's 3D Animated Facial Expressions

Transcript of my informative speech on how PDI/DreamWorks' masterpiece revolutionized facial rigging and expressions in 3D animation

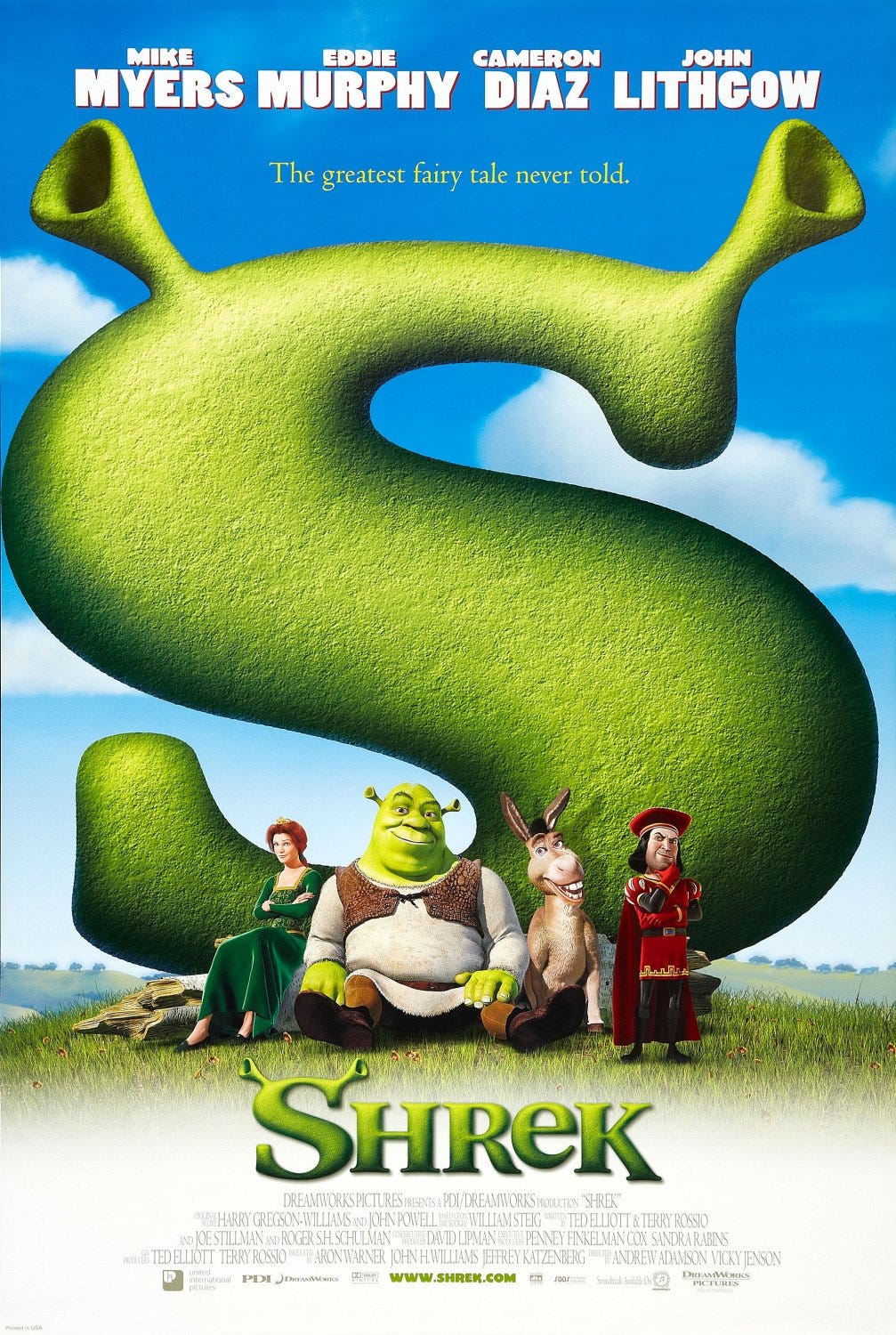

“Once upon a time, in a land not so far away, over 275 people were given a daunting task. They had to transform 0s and 1s into a rich landscape filled with creatures who would tell a tale so fascinating and funny that millions of citizens would leave their homes to go see it. The 275 people huffed and they puffed [until] an enchanting world [slowly] began to take shape. And then, as if by magic, over 3 years later, those 0s and 1s were completely transformed into a hilarious movie called Shrek” (Robertson, 2001).

I’m hoping you all know the film I’m talking about.

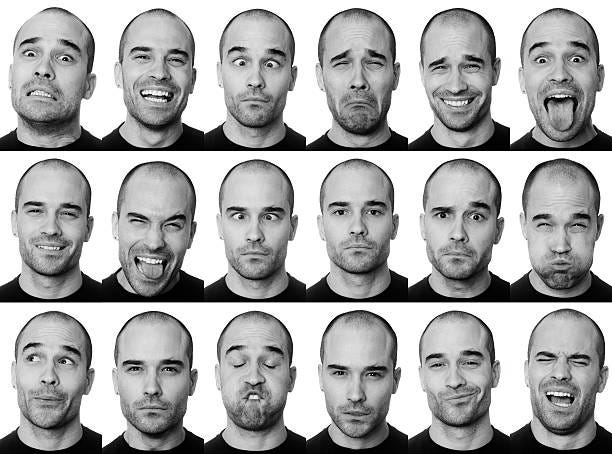

If so, you’ll be able to recognize this face right away and recall the context of Shrek’s expression:

But.. how about now? Does this look like the version of Shrek you’re familiar with?

Besides his obviously blown up face, there seems to be something wrong with this Shrek. Despite looking like his original counterpart at first, he has soulless eyes and lacks character in his expression.

Being an animation enthusiast and hobby animator myself, I’m well aware of the fact that it’s details like this that can make or break a film’s ability to empathize its characters to the audience.

Thus, a large part of why Shrek is my favorite movie—aside from its great story, characters, message, music, and virtually everything else—is its place in the advancement of facial expressions in computer animation.

To give you all insight into this fascination of mine, I will be overviewing the importance of believable facial rigging and movements in 3D animation while relating to Shrek’s technical production.

As we just saw from my comparison of two Shrek animations, facial performance is essential to creating characters that can communicate strong emotions and garner the same from an audience. This makes facial animation a “powerful storytelling instrument in the Entertainment Industry,” but it is hard to achieve (Orvalho et al., 2012).

Why? Well… “Every day, we see many faces and interact with them in various ways: talking, listening, looking, making expressions” (Orvalho et al., 2012). As a result, most of us possess a keen ability to identify unnatural behavior.

Given that any audience member can quickly spot the tiniest errors in "face shape, proportion, skin texture, or movement" and are essentially "experts in detecting expressions" (Orvalho et al., 2012), filmmakers—especially those working in hyperrealistic mediums—are confronted with a significant challenge.

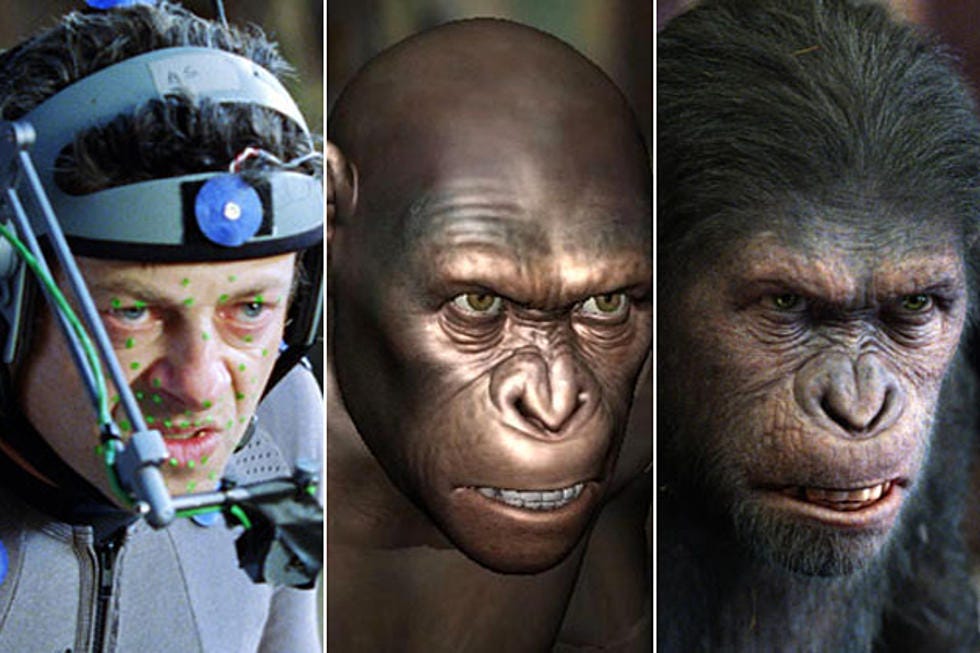

To effectively recreate the nuances of human expression in a character, filmmakers typically have two prominent approaches at their disposal: motion capture and keyframe animation.

What is motion capture?

Motion capture, or MoCap, is the creation and animation of a digital facial mesh by attaching scanning range sensors to an actor and using the 2D or 3D positions of the markers to animate the rig.

Think of it as the 3D counterpart of rotoscoping in 2D animation. It captures movement data quickly but can introduce an uncanny, hyperrealistic quality to the final product.

A prime example of MoCap’s use is in James Cameron’s Avatar, where “performers [wore] miniature computerized motion sensors near joints and facial areas to capture the movements and facial muscle nuances that occur with each gesture, motion or expression” (Avatar, 2020).

Interestingly, in the case of Shrek, motion capture was initially going to be used for the film. However, when Jeffrey Katzenberg, then CEO of DreamWorks Animation, viewed a test reel, he hated it so much that he subsequently “fired everybody involved” (Jones, 2021).

Evan-Jones: Motion capture was in the air. The 2D people used to call it the devil's rotoscope. Rotoscope is how they used to do Disney stuff.

Adamson: The very first meeting I went to was the motion capture test.

Evan-Jones: It was basically going to be shot motion-capture by these guys called the Propellerheads. There were the three guys we knew [Rob Lotterman, Loren Soman, Andy Waisler]; then there was this other guy back in New York, who was the writer. It turned out the writer was J.J. Abrams. Abrams wrote the test we did motion-capture on. It was, like, 45 seconds. What they wanted to do was use puppets for the four-legged characters. They had people in fat suits. And it was just a big fat mess. It was a Shrek character that was not the same but not dissimilar to the one we ended up seeing in the movie: guy in a fat suit walking through an alley in a town and then he's mugged by this character they called the Mugger. Shrek was accompanied by the donkey, who was played by a person using their feet for the back legs and brooms for the front legs.

Adamson: Jeffrey really came from animation and didn't like a lot of what was going on, so he rejected it outright and kind of fired everybody involved.

Evan-Jones: It was before they really had the computing power to do it properly. It was actually more data than they could cope with.

Hegedus: I made a suggestion that we do miniature sets with CG animation. So we did a little 10-second test with Illusion Arts that was designed to show a miniature set, including matte painting with a maquette stand-in of Shrek. That was presented and well received. It was beautiful.

That left Shrek to its second option: CG keyframe animation to be completed by Pacific Data Images (Jones, 2021).

What is keyframe animation?

Unlike motion capture, which depends on image tracking and geometric data acquisition, keyframe animation is more reliant on artists’ skills and facial rig design. It involves using splines that connect a series of spatial control points and enables the adjustment of key parameters at these points to control animation over time (Orvalho et al., 2012).

To capture all the details and subtleties of an expression, a broader array of tools, like “deformers to simulate soft tissue and muscles, more joints to influence region[s] of the face, and implementation of controls to manipulate head structures and secondary face regions” are typically created and used (Orvalho et al., 2012).

Shrek‘s facial animation system revolutionized the way animators convey intricate emotions and expressions through a layered approach based on real human anatomy.

To break it down, a character’s skull was first formed in a computer and covered with computer recreations of the actual facial muscles. A layer of skin was then applied and programmed to respond to the manipulations of the muscles, mimicking the behavior of a human face.

The end result? A dynamic representation complete with natural wrinkles, laugh lines, and other subtle imperfections, enhancing the authenticity of the characters' expressions (Robertson, 2001).

A breakthrough program called a ‘shaper’ also played a pivotal role in enabling intricate facial and body movements. The ‘shaper’ functions by internally altering a character’s surface structure (Adamson et al., 2006).

“In terms of things that we actually invented, there was a new technology called ‘shapers’ that we put together, which was a much better way of doing deformations of geometry. So any time a character is bending, and you’re trying to deal with what happens, where that bend is taking place, and the way that the muscles work, that’s what shapers are all about and those are underlying everything in the main characters.”

-Ken Pearce, director of animation software development

This innovation produced remarkable outcomes. For example, when an animator turned Shrek’s head, wrinkles would automatically form on the back of his neck.

Recognizing the potential to extend the principles of facial animation controls to the entire body, this program paved the way for more authentic body movements as well.

Furthermore, Shrek’s facial animation system contained high-level controls that allowed animators to manipulate several animation controls at once (Robertson, 2001). Primary and secondary characters used the same facial setup (though not without specific adjustments), which had between 100-200 animation controls (Robertson, 2001) and this allowed for the variety and believability of facial expressions throughout the film.

“We’re trying to create a tool that has a sort of a presentation and an interface to an animator so that when they are working with this, they’re thinking, ‘Okay, now I’m making this character look mad in a way that shows he’s also embarrassed and he’s embarrassed because he’s been caught lying.’ So that’s a very particular, nuanced kind of mad.”

-Ken Pearce, director of animation software development

"Shrek is an ogre, but at the same time, he has the same range of emotions as any of us. In fact, the most challenging animation to do was when Shrek is hiding what he is really feeling—saying one thing but thinking something else. Animators are just like actors; it's up to us to put all those emotions into the face."

-Raman Hui, supervising animator

Shrek marked a historic milestone as the first computer-animated film to feature human-like characters, and it executed this endeavor with remarkable success.

As we now know, the generation of realistic facial expressions in animation was—and still is—not easy to harness, and the dedication of the Shrek production team to keyframe its characters and develop pioneering technology for the film is a testament to their commitment to bringing this fairytale world to life.

I encourage all of you to go and watch a 3D-animated film and analyze its characters’ facial expressions. Do the characters suffer from Uncanny Valley syndrome? Or do they move in a way that feels real?

“Character animation isn’t the fact that an object looks like a character or has a face and hands. Character animation is when an object moves like it is alive, when it moves like it is thinking and all its movements are generated by its own thought processes… It is the thinking that gives the illusion of life. It is the life that gives meaning to the expression. As Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wrote, ‘It’s not the eyes, but the glance—not the lips, but the smile.’”

-John Lasseter (Catmull & Wallace, 2014)

Reference List

Adamson, A., Jenson, V., Myers, M., Murphy, E., Diaz, C., Lithgow, J., & Steig, W. (2006).

Shrek. Full frame format. Universal City, CA, DreamWorks Home Entertainment.

Avatar. (2020). Humane Hollywood. https://humanehollywood.org/production/avatar/#:~:text=This%20film%20was%20created%20using,each%20gesture%2C%20motion%20or%20expression.

Catmull E. & Wallace A. (2014). Creativity, Inc.: overcoming the unseen forces that stand in the

way of true inspiration. Random House.

Jones, R. (2021). The oral history of 'Shrek,' the "ugly stepsister" that changed animation.

Inverse. https://www.inverse.com/entertainment/shrek-oral-history

Modesto, L., & Walsh, D. (2014). DreamWorks animation's face system, a historical perspective:

from ANTZ and Shrek to Mr. Peabody & Sherman. ACM Digital Library, 37, 1.

https://doi.org/10.1145/2614106.2614131

Orvalho, V.C., Bastos, P., Parke, F.I., Oliveira, B., & Alvarez, X. (2012). A Facial Rigging

Survey. Eurographics.

Robertson, B. (2001). Medieval Magic. Computer Graphics World, 24(4), 24.